The Strength and Skills of a Rare Originality

Debesh Roy

Amarendra Chakravorty’s novel ‘Bishaadgatha’ (A Melancholy Song) falls far beyond our habits and expectations of stories and novels and the ideas generated by those habits and expectations. As is the case with novel-turned-films, art forms too enjoy a mixed readership-viewership and a larger popular appeal. And these readers-viewers determine to a large extent the expectations or habits with which we approach an art form. These very same set of expectations often habitually turn into norms. To be able to break such norms, especially of popular forms, is not an easy task....It is almost as if for those who write fiction, a unique stylistical use of language becomes an obstacle to writing. Almost as if stylistic singularity goes against the norm. Structure, twists, events, ending – it is through these that the prose writers differentiate themselves. Or, in a way, it is in these that their differences cannot be erased. The opposite perhaps also holds true – in their own way fiction writers clue in to the structures, twists, events and endings that their readers expect of them. Suicides by fiction writers in bangla are mostly the result of such expectations.

Amarendra Chakravorty has created this novel with an evolved self awareness, an awareness that is rarely found among novelists writing in bangla. A sign of that awareness – having read the nearly 275 pages of the novel, no reader will be able to single out the main theme, or rather the storyline, or pinpoint the main character.

Such novels, about a range of characters, are not that rare but usually the novelists then tend to focus on establishing connections between the actions, activities and relationships between the many characters and keeping those connections alive. The number of characters in Amarendra’s novel is endless. Even the person whose movements have ended within a span of a few lines, has a name. Not a single character is left nameless.

The sites of action in the novel are not that many in number but they too have their specific names, and each is marked by incidents. Any reader can easily draw out a map of the locations. Instead of leaving it to an imagined reader, let me admit that I myself had drawn out such a map – so that I could understand how the most concrete characters in the novel – the places – have been developed according to a design. Am glad to admit that the novel’s most consistent and stable reference points are these places on the map. It is these very fixed and recurring places that connect the countless characters in the novel and given space to the many self-contained incidents that are strewn across almost every page. Had I not charted out the map as a sort of a reading support, it would been difficult to, no impossible to, find a core for the endless stream of incidents, characters and unresolved movements. Why look for such a core or centre – when the author is so keen on keeping that untraceable? Not secret, but untraceable.

Probably because it is my nature when it comes to reading literature or following a work of art. Every work of art must have a centre, not in terms of content. But of form. The centre does not lie in the content of the painting, the song or the piece of writing. It emanates from the frame canvas itself, or the vocal throw or a word filled page. Not that I have never not come across a central point. Or not found one made overtly available. I detected that centre within the first few lines in this novel, within 68 lines to be specific, to come to my aid later when am more deeply immersed. So that when I had gone much deeper, I could return to the beginning and see that the author had sketched out the novel’s central point right at its beginning – ‘Balisona village’, ‘the infinite green of the Balisona region, ‘will be slowly made desolate over the next forty-forty-five years’, ‘when new legends around the lost river would come into being’, and the condition of the Chowdhury household and the villagers of Balisona: from ‘the wife of the headmaster of the free primary school’ to ‘a few more women on the verge of delivery started pouring out their milk-and-bread rations stealthily, into cans brought over by their children from home’. The novel has never strayed from its central focus on physical location. Many, from far far away, from faraway countries and seas, have converged in this novel. Many have died upon entering this novel, in fact a large number of people from the former zamindar Chowdhury household have left the novel’s space, voluntarily – for far away places, countries and seas. And they have returned again to Balisona, voluntarily, as if their long migrations were nothing but a path leading them back to Balisona.

But this novel is not a legend or a fairytale; not even for adults. Most events in the novel are set within a contemporary timeframe. Many of which are contradictory, as for us, or for the novel when it was being created, but contemporary. The author has underlined this contemporary nature of the events so often that no way can it escape a reader. But when the author refrains from explaining these events and even their counter events, an element of the oppositional arises. As if Balisona village is changing, as if the extinct river is being revived, as if to claim a share of that change many people of many interests, even foreign investments, are converging at Balisona and as if from within Balisona rises an exploration of its own true nature like a collective morning hymn, through the journalistic reports of Parikkhit’s ‘A Melancholy Song’, through the many activities of Lalkamal-Nilkamal and we wonder whether these are silent condemnations. In this exploration of its own true nature, many of Balisona’s dead join in and even the living can converse with the dead on the subject. I have already mentioned my obsession with pinpointing a central core for any work of art. My other obsession is with finding its expanse. In the novel that expanse is created through its inner and outer involvements.

The concentrated design with which Amarendra has created this novel is proved -- by the fact that not once does he mention this expanse. Nor circumference it in terms of events. The novel ends on a note of an absence of resolution...A novel like this reconfigures the novel form. Amarendra has succeeded here – this has been carried through not only by his personal skills and strengths, but also because the new possibility that the bangla novel is experiencing at this point in time.

( Originally published in Anandabazar Patrika, 27/08/2016 )

Dr Amiya Deb on Bishadgatha (Melancoly Ballad)

The novel, 'Bishadgatha' tells the story of a village, which had got a river flowing through it. Long ago the stream dried up leaving behind a wetland. Once an enormously powerful Zamindar, the grandfather of the presently landless Chowdhuris, got seven rebel peasants murdered and buried in that wetland. That bygone incident controls the entire novel with its magic reality. One day the skeletons of the seven peasants were exposed in the dried riverbed, when it was dug for the lost channel or for gold. Although 2-3 generations old, the incident has its impact in the times of the novel (The very first occurrence being the brutal rape of one of the daughters of the Chowdhuris by two descendants of the rebel peasants), which again follows three subsequent generations in its storyline. In course of unfolding the story, the skeletons of the peasants not only resurfaced on digging the wetland, they even began to make appearance in daily dream of one Chowdhuri, who had initiated the excavation.

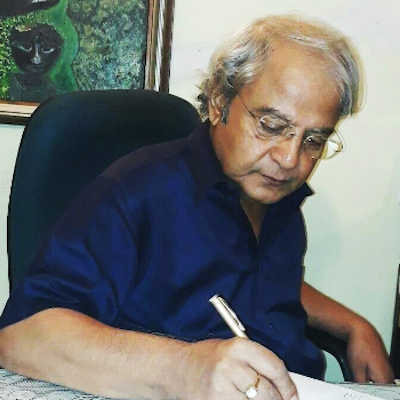

The novel has acquired its name from the title of a weekly newspaper column mentioned therein, and written by Parikshit, the central character of the novel. In his column Parikshit writes about social issues, issues that hurt him and humanity, concerns common people, whom the rulers consider as the undisputed enemy. The gloomy beholder portrayed on the cover of this novel represents him. The novel has no hero as such, though the regulatory force is Parikshit, the writer of the column named 'Bishadgatha'.

The reason that the novel 'Bishadgatha' by Amarendra Chakravorty is worth mentioning is, its intricate weaving of the story extended over years through many characters.

Sumita Chakraborty on Bishadgatha

(Retired proffesor, Burdwan University and eminnent literary critic)

Amarendra Chakraborty is said to be a versatile man and a man of many talents. I would like to highlight a few aspects of his persona. He is a world traveler. He has visited many countries. The names of his travelogue are 'Sumerubrittey Bhraman (Travel in the Arctic Circle)', 'Bandhubhara Basundhara (A World Full of Friends)', 'Pahari Gorilla-r Khonje (In Search of the Mountain Gorillas)'.

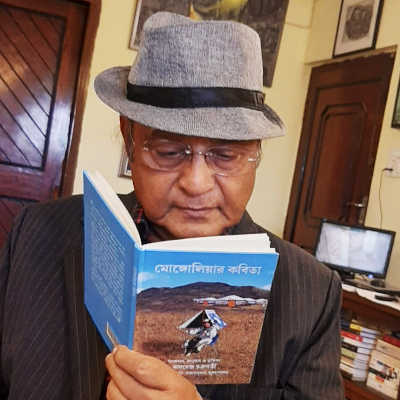

Amarendra Chakraborty, an expert in photography, has also been filming his tours from very beginning and these films have a long history of Doordarshan broadcast. Rare are people who have visited Antarctica, Alaska, Africa, Mongolia, China, Myanmar, Jordan, Israel, Egypt, Indonesia, Bulgaria and many more countries.

'Bhraman'-- the travel magazine which he founded is an extremely popular magazine and He is currently the Editor-in-Chief of that high quality journal.

He is also a painter, having had solo exhibitions more than once.

A novelist, photographer and a painter at the same time, make the novelist a little special. Because in his novel, the narrative of photography can easily mingle with the imaginative details of paintings. One should keep in mind that, the surreal fantasy is created by breaking the reality of photography. The novel also adopts this style as happenes in cases of those by especially the Latin American writers, who showed the way and in many other novels of present time and also in Amarendra Chakravorty's 'Bishadgatha'. The reader must be prepared for this experience before reading this novel.

But Amarendra Chakraborty has many more identities. He has felt the struggle for human survival from the very root of it. Is there any doubt that the main crisis of human life is the crisis of earning money? Why on earth a writer and traveller like Chakrovorty would edit magazines like Karmakshetra (First published in 1980) and Peshaprobesh if not he felt the crisis of existence of a man without minimal earning?

Long back in 1966, this fugitive student of the comparative literature department of Jadavpur University, has been able to keep his name immortal in the history of Bengali literature when he edited a magazine called 'Kabita-Parichay'. In 1967, at that very young age, he edited 'Saaraswat Prakash' magazine jointly with Dilip Kumar Gupta. Later he published a literary magazine called 'Kaaler Kastipathar'.

There is another side to this man. Probably his first writing attempts were for children. The target readers for 'Shada Ghora'(The White Horse, pub.1971), 'Rishikumar' (1979), 'Hiru Dakat' (Hiru the Decoit, pub.1986), 'Gaur Jajabar' (The Wanderer Named Gour, pub. 1991), 'Bhooter Bashi' (The Flute of the Ghost, pub. 2002) etc. are children. He is also the founding editor of a magazine called 'Chhelebela' ('Childhood days' First published in 1982). There are many writers who write for children, but not writers for children. But when Amarendra Chakravorty wrote these books, he felt what were on the minds of the children.

Amarendra himself wrote poetry. From 'Bikshata Anweshan (The Tormented Quest)', 'Nadi Jaane, Kachi Neempatarao Jaane (River Knows, Tender Neem Leaves Also Know)', 'Mrityur Odhik Ei Mere Fela (A Murder, Far More Than Death)', 'Bhumikamper Raat (The Night of Earthquake)' are a few collections of his poems. One should mention his ‘Kshaner Bachan (Words of the Moment)’, written in the style of Sanskrita Shlokas of two-four lines.

Now the question is how did he do so much work? How could he? And why?

This can only be guessed at. I think, his eagerness for world-travel is the source of this versatility. He has seen the universe. So many different people are inhabitating in every corner of this strange world, which is full of different cultures and lifestyles and folklores. But everywhere the human innerself is same.

That's why he finally came to the novel. Because novel is the format that seeks to capture life in all its dimensions. His first novel is 'Bishadgatha (The Melancholy Ballad)', published in 2013.

If it is to be compared with any other novel, then it is Debesh Roy's 'Tistaparer Brittanto'. The subject matter of both novels is somewhat superficial.

On the first page of 'Bishadgatha', a village is mentioned, named Balisona. A river is also mentioned on the first page. Drying river — which was flowing even a hundred years ago. According to local legend, Behula went to Indra's meeting with Lakhinder onboard a raft sailing through this river. According to some, along this river went Chand Saudagar's trade voyage. That river is now a dry field.

Although a region cannot move back and forth physically, but it has a mobility with the passage of time. The spread of time in the novel is more than two centuries. But the format of that time is not chronological. The currents constantly merge in different streams and at different levels. Past and Present do not flow parallelly, nor there is any Flash-back. Thus the combination of time became somewhat difficult for the reader.

The narrator starts telling the tale with the memory of the river that died on the east side of the village. That memoir is many years old-- atleast hundred years. But when he says, by that time India barely had achieved Freedom. Because in the very first paragraph an incident of birth in a rural hospital is mentioned. The reader has to understand that this novel wants to give a vivid picture of Bengali society of half a century post Independence. When the narrator narrates, every once in a while the pictures of these fifty years come up in different pieces. It is better to say 'moving picture' than 'picture'. But one picture does not last long. It would not be right to say that the present, near-past, distant-past, lost-past, happening present and presumed future are mixed as collage. It should be said-- a moving collage is floating, turning, coming back, breaking, forming again-- making the novel 'kaleidoscopic' in true sense. There is mentioning of refugees. The mass flow on Indian soil which became apparent for long or occasionally even after 1947-50, also comes to the fore from the pages of the novel.

There are many more characters in the novel. Alone they might not be important, but the place Balisona is costituted with all of them.

Towards the end of the novel, the central character dies, but that death does not end the struggle for human ideals. The faith and confidence entrusted upon the younger generation is a bright aspect of this novel-- a reflection of the its creator's mind.

Some critics have noticed the use of magic-reality in the sense that, real and miraculous events often merge in the novel.

Another attraction of this novel is the poetic nature of the language. But poetic language is not very new in Bengali literature. What we like more is, the eternal fragrance of deep love, the manifestation of gentle light in the hearts of the young, and sometime of the old. 'Bishadgatha' can also be read as a novel of love.

'Bishadgatha' begins with the context of Balisona's river. Ambareesh has hired workers to bring the river back. But the task has not been proved that simple. Ambareesh's whole life has been spent in the determination of digging the riverbed back to its real self. It is not clearly stated in the novel, if the river came back atall. At the end of the novel, people's suffering due to the cruelty of the ruling power has become bigger. The river Balisona has become a river of blood. The scene of Lalkamal and Nilkamal shot dead on the bank of it, is the last scene of the novel. The namesake characters in Bengali Fairytale even could not conquer death. But in 'Bishadgatha' the strength of the fierce struggle of life overwhelms all of sadness.

Amarendra Chakraborty will stay distinguished among Bengali novelists for his novel 'Bishadgatha'. (Excerpts)